Film Notes from England (1960s)

Peter Davis reflects on his time in England making films from Public School to Anatomy Of Violence.

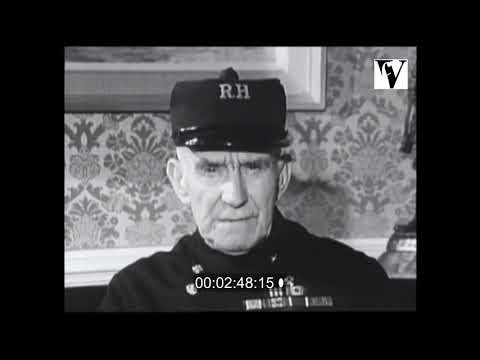

Peter Davis on the grounds of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, 1966

The advantages of a Public School education – advantages based not on any inherent virtue in the system of private education, but rather on wealth and influence, and overwhelmingly on the Old Boy network are still glaringly there, even if the upper class accent has adopted working class inflexions.

The British educational system came up again (after Shadowplay) in the early ‘Sixties when, together with my working partner Staffan Lamm, we planned a series of English documentaries for Swedish Television (I was living in Sweden at that time). We decided we would make a film about a public school, and were able to gain access for this purpose to Hurstpierpoint in Sussex.

I don’t know how we came to choose Hurstpierpoint in Sussex for our documentary; we certainly would have wanted one of the less well-known public schools. I suppose the most famous depiction of a public school is Lindsay Anderson’s If, which now I come to think of it, is invested with the rebellious element of Shadowplay, although modesty prevents me from claiming any influence. Anderson’s fantasy is a more anarchic challenge to the public school system, with its machine-gun slaughter at the end. If is of course a savage satire on Kipling’s poem of the same name about what it take to become a man. And that is precisely what the Public School system was supposed to do. What it did do superlatively well was produce a brand dedicated to maintaining a class system. When we went to film at Hurstpierpoint, after all the indoctrination I had received through the Boys’ Own Paper, Goodbye, Mister Chips, The Browning Version, what surprised me most was the limitation on the boys’ freedom.

The cadet tradition testified that regimentation was a part of life, but beyond that, the boys were confined to the school most of the time, day and night, always in a group, always subject to school rules of conduct. In contrast, my own boyhood had been one of great personal freedom, with many choices of how to dispose of my time, once homework was done. We were in fact the privileged boys.

Chelsea Bridge Boys

Freedom may be the unconscious theme of Chelsea Bridge Boys – the freedom the young men and women generating from the mobility of the machines they rode. If you are genre-inclined, you can see the film as a road movie confined to city streets, with none of the open road liberty of American films. I remember as a stupid young man without a helmet straddling the pinion to shoot as one of the bikers attained a hundred miles per hour as he hit the south end of Chelsea Bridge – the theory being that if you braked at that point, running at that speed, you would stop by the time you hit the traffic light at the other end of the bridge.

Pub

I don’t recall how I got the idea to do Pub, which dates from 1961. It was the second documentary I did for Swedish Television, and it came at a time when similar slice-of-life “neutral” documentaries were being made in Britain and in Sweden. Swedish TV had nothing to lose by financing it, it cost them practically nothing. For me, it was a way of revisiting my origins in Bethnal Green – the Approach Tavern was located in the block on Approach Road next to the one where I was born (delivered by my grandmother, who was a midwife).

My father was friendly with the family that ran the Approach for reasons that had nothing to do with its trade, for my family was teetotal – although my mother and grandmother were known to sneak a glass of sherry at Christmas. The Approach had a special memory for me, for early on in the war, my grandmother took me to the pictures one afternoon, and when we got back, found that the Approach had been bombed. The East End was particularly vulnerable to attack as it harboured the docks, and the German pilots could follow the silver line of the Thames. I think the Approach was the first pub to be hit in that war.

Then I was evacuated, being reunited with my parents later on in the war when they moved out of London to Wallington, in Surrey, where I would make Shadowplay. In the East End, we had a very large extended family which was very close. Amazingly, this was maintained into the postwar years when this extended family moved out of London, with most of them settling within an easy bike ride from where we lived. There was constant visiting back and forth, with never any sense of inconvenience, or being unwelcome.

Immigrants

Going back to the East End in later years it was to find that the lower-class population that was relocated after the war was being replaced by coloured immigrants; I think that the film Immigrants, made by Staffan Lamm and myself was one of the first attempts to look at the new Britons.

Certainly in the East End, racist graffiti were everywhere, but even more specious was the prevalence of unconscious racist images, like the golliwog marmalade, and the Black-&-White minstrel show on television, and projections of evil asians – now morphed into evil Muslims, of course. When we interviewed the Metropolitan Police, we asked the spokesman why there were no black policemen; “Oh, they don’t usually measure up to our height standards” was the bland reply.

I had been brought up in a pre-World War II Britain that was unashamedly racist, although at home in England this did not find concrete form until Commonwealth immigrants started to flood in. It was also a country obsessed with an organic imperialism, part of the structure of society. It glorified the army, revelled in past conquests, recited past battles, wallowed in an entirely sick reverence for the sacrifices of the First World War which left untouched any serious questioning of its conduct or necessity. Statues glorifying the warrior image abound in London. Some of these thoughts must have been in our heads when we chose the retirement home for soldiers, the Royal Hospital, as a fit subject for one of what we called for our Swedish audience English Sketches.

Royal Hospital

My strongest impression from Royal Hospital was a sense of the relationship between the military and the economy. One of our interviewees said that the choice for him as a young man was either to join the army or starve. And I can’t help reflecting how easy it was for the Germans to re-arm and remobilize in the ‘Thirties because of the abundance of young men who simply had no other employment choices. To take a leap to the present day, the real unemployment rate in the United States is probably in excess of 20%, which means there is an abundance of young men and women who find employment in the armed forces, with their decent pay, health benefits, training useful even outside the military, to be an attractive option, even the only option. Remember that the Vietnam War was brought to a halt because of the rebellion of young men against forced conscription; America can fight in Iraq and Afghanistan yesterday, and possibly in Iran tomorrow, because it has abolished conscription. Britain’s empire was built by mercenaries, many of whom were nonetheless convinced they were serving their country.

Strip

What to say about Strip? I was working in London with an American friend Don Defina at that time, and we got access to the Phoenix Club in Soho because of my oldest brother’s connections. I had never been to a strip club before, and so this was my first exposure to an abundance of female flesh. It proved all too workwomanlike to be either intimidating or prurient. The girls accepted us - Staffan, Don and myself - readily, and then some of them quite quickly got tired of us, and we had to stop. We managed to shoot for fewer than three days, we had equipment problems, we had a minimal amount of film – I would be surprised if our shooting ratio was higher than 4 to 1. Staffan had to go back to Stockholm, so Don and I edited overnight in an editing-room we got for nothing. Working from 8 Sat night to 6.30 the next morning, we produced the cut you see. Watching it now, I think it’s not half bad. The girls might even thank us for it.

Strip, unlike the other English Sketches, was turned down by Swedish TV because it was too nude. Even with Sweden’s sexual liberality, it was before it’s time. It was distibuted by Derek Hill through his Short Film Service in Soho, but I don’t recall that it ever made any money, which is pretty much true of all the English films. Come to think of it, of most of my films…

Dialectics of Liberation - Anatomy of Violence

When I came back to UK in 1966, I had trouble finding work because I was not a union member, and the film union was a closed shop. I was finally hired as one of a group of four young directors by Rediffusion Television, each to do a documentary of his own choosing.

Mine was on the 1910 Welsh miner’s strike. However, before I could begin shooting, one of the directors had gone so far over budget that there was no more money left for the other shows. This effectively ended my prospects in Britain. But in 1967, I did manage to persuade WNET, New York’s public television station, to let me do a documentary on the grandiosely named Congress on the Dialectics of Liberation and the Demystification of Violence, a motley gathering of vaguely and definitely leftwing intellectuals and activists, pacifists, scientists, and counter-culture people.

This unique congregation was International, but heavily seeded by Americans – Allen Ginsberg, Stokely Carmichael, Paul Goodman, Paul Sweezy, the German-American Herbert Marcuse, among others. Out of this came my documentary Anatomy of Violence, which was in fact as good a way as any to segway into the heady atmosphere of American politics at that time. In many ways, I regard the Dialectics as the last inhalation before the last gasp of the American Left. The exhalation I would find when I settled in New York after being offered work there by an old friend.

The last gasp, filled with hope, histrionics, courage and comedy, came with the union of the Left and the counter-culture against the American war in Vietnam, and the victory at home that helped to stop that war. But it proved to be a Pyrrhic victory.